Free Resources

Free Resources

Exercitation ullamco laboris nisiut aliqu exeaea commo. Duisltrtohg aute irure.

Alivin Corondo

Networking Lead

Exercitation ullamco laboris nisiut aliqu exeaea commo. Duisltrtohg aute irure.

Stepha Kruse

Design Lead

Exercitation ullamco laboris nisiut aliqu exeaea commo. Duisltrtohg aute irure.

Dunican keithly

Networking Lead

Downloads

Choice Theory

Mind-Awareness and Life Management

We steer our lives through the activity of our brain and the inclinations of our mind.

If we want to manage our life well, it's helpful to be mind-aware: to know enough about how our mental equipment works, to guide ourselves through the unpredictability and challenge of day-to day living.

Whether we realise it or not, we all make assumptions about how our mental processes work. On this website I aim to provide an explanation that is both simple and liberating: every dimension of this explanation will provide you with opportunities to manage your mind - and your life.

As you read on you will discover:

- 1. We are internally controlled.

- 2. Our perceptions are self-created.

- 3. How brain and mind work.

- 4. Why we are motivated to do what we do.

- 5. Our behaviours act on the world around us.

- 6. How to steer your life - using the information gleaned from Choice Theory.

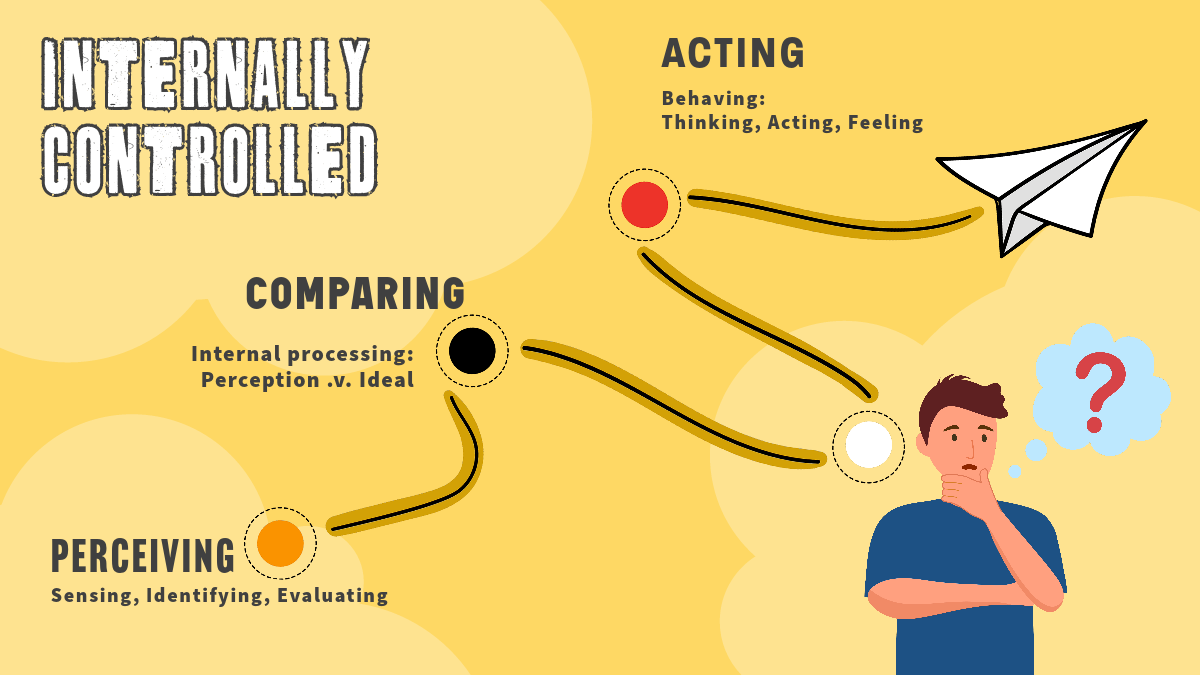

1. We are internally controlled!

This explanation of human behaviour is based on Choice Theory, a psychology of internal control. That means that whatever is happening around us, it is the choices we make 'inside' ourselves that control our behaviours.

It often seems as though the events and people around us are overwhelming us, but they can't and don't actually control us. Our brain, and the mind that emanates from it, are inside the bag of skin we call self. These are the elements of our control system.

Of course, we are not cut off from the world. We acquire information from outside ourselves through the 'windows' in our bag of skin, our five senses. Sight and hearing, taste, smell, and touch come into our body as packets of energy - such as light hitting our retina, or sound vibrating against our ear mechanism. Our internal perceptions translate these into symbolic energy such as images and language. We don't receive even this information without further translation: ourinternal processing occurs by connecting the raw symbolic data to particulars that are already in our memory and experience.

How it Works

There are essentially three activities that make up this internal processing:

Our Perceptual System takes in information and interprets it.

We compare the resulting perception with how we would like things to be.

We choose a behaviour that will bring us closer to what we want – or one that will avoid pain.

Because only the external event and the resulting behaviour are visible, many people ignore the internal nature of our control system. The internal processing of other people is hidden, and sometimes we are not mind-aware enough to understand what is happening inside ourselves.

Each part of our internal processing is accessible to us. We can make choices about how to perceive people and events, what to compare with and what behaviour to respond with. Becoming aware of the degree of our own control it is liberating. It means that we are never helpless. However challenging the circumstances we face, we always have choices.

Please don't misunderstand this. I am not for a moment suggesting we have unlimited choices. Adversity may limit our choices. We may not always have attractive options, but we always have some choice. As Victor Frankl wrote in 'Man's Search for Meaning' even those imprisoned in the Nazi Concentration Camps, though they were starving and faced with death in the gas chambers, were not deprived of free will. These men and women could still choose their attitude; though in extremis they could still choose how to treat their fellow prisoners and their guards.

Knowing that we are the only author of our behavioural script is empowering. Other people's behaviour and external events can influence us, but we are the ones in control!

Why it Matters

Managing our lives feels very different when we accept our circumstances and take responsibility for whatever choices we have.

We no longer need to feel helpless in the face of unpleasant events or troublesome people. We can adopt an ACT mentality:

ACT is a model for self-disciplined acceptance and problem solving.

Accept the situation.

Whatever happened, or is about to happen, accept what cannot be changed. Especially accept that you, like every other persona is less than perfect. You miss opportunities and sometimes neglect the things that your best self would take action on. In the same way accept what others have done.There is little point in blaming, complaining, or making excuses. None of us have a magic wand that enables us to go back into the past and make changes. What is done is done. Accepting the situation liberates us to move on.

Consider the CHOICES you DO have.

Once the situation, is accepted you canconsider what choices you do have. In some situations, the only choice we have is to ask for forgiveness, forgive yourself, and to do your best to make things right from this moment Never fudge it or pretend. Choose whatever will work best to make things right.

In other situations, when other people or events have brought us pain, accepting whatever has happened is the key. If we can improve the situation though our own choices, we should. If not, we still have choices, opportunities to mould our own future and influence what happens next. As Victor Frankl observed: 'Life ultimately means taking the responsibility to find the answer to the problems it presents.' Life does present problems but always presents choices.

Take Action.

Decisions are only really made when action is taken. Whatever you choose to do, either do it at once (if that is possible), or else make a clear plan of when and how you will take action. Intentions are never enough. Many people form intentions but don't take the next step. They allow themselves to be paralysed by their own negative self-talk and then delay, put off and find reasons not to act. Take action, even if it is does not work out perfectly. Mistakes are the foundations of learning.

ACT is a powerful model for supporting our own resilience by helping us to move on quickly from negative events and problems, and for helping us to be future-focused and solution-oriented in our relationship with ourself and with other people.

Knowing that we are in control even when things are difficult, and using ACT supports our resilience.

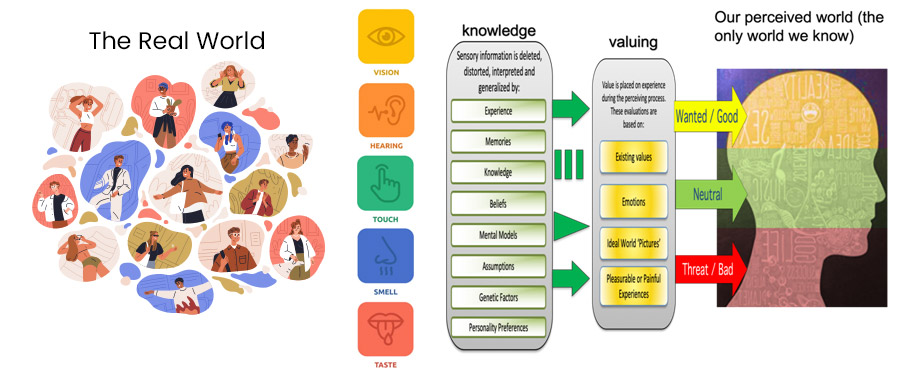

2. Our Perceptions are self-created.

As mentioned in the previous section, our perception of people and events is created by active interpretation. It is not the passive receipt of information. We receive information through our senses but decipher it through the lenses of what we already know. Our past experiences, our beliefs or prejudices, our fears and hopes all play a part in how we see the world.

How it Works

We take in information through our 5 senses, but the information enters our brain as unprocessed data: simply packets of energy in the form of light, sound, or sensation.

We then apply the information we have stored in our memories and translate the raw energy into meaning. For example, when visual information matches something in our memory, we can give it a name and recognise its purpose. We might see fragments of rainbow in the sky. When we were children we might have been told that there was treasure at the end of the rainbow and so that is what we believed. As we acquire new information we realise that what we are seeing is sunlight through water droplets refracted into seven different colours. The rainbow does not change, but our information changes what we know about it.

In the same way, two people can see and hear the same person, but one see them as a threat and the other see them as a hero. The difference is not just in how we evaluate the world – though as you can see from the diagram above, the value we place on things does play a big part in how people or events are perceived. However, with different life experiences, different knowledge, different assumptions and beliefs about the person and their motives the same individual is perceived is widely different ways. The same level of variation is apparent in almost every perception. It explains the very different ways that we see the world explains the widespread degree of conflict in human relationships. As the cliché tells us, we see things not how they are, but how we are.

Why it Matters

As the diagram above shows, our emotions play a big part in our perceptions. As we take in information from the world around us, the most primitive area of the brain alerts us to danger and these danger signals reach the emotional brain before the cognitive brain. We feel the fear before we process the thought about what we are afraid of.

Fear can be useful, it protects us. However, as anyone who has ever been startled by a kitten in the dark can tell you, the emotional brain can mislead us. This is especially true of our perceptions of the people around us and the way we relate to them. Humana extend their need for physical survival to social survival. We are always alert to threats to our status, certainty, autonomy, relationships, and sense of fairness.

Mind-awareness, knowing that we construct our own version of the world around us is significant in two major ways:

- It means that we can critically evaluate our own perceptions. Just because something feels right does not always make it right.

- It means that we can question and challenge our own self-perceptions (see below). We can easily be misled by the negative messages we hear from others and say to ourselves.

- It offers us a shield against intolerance. It's healthy to accept that the different ways other people see things are not wrong just because they are different.

Self-Perception

In the way we assemble all of our perceptions of the world, our perceptions of self are constructed from fragments of our own experience. Then these perceptions become assumptions -which in turn become pre-suppositions. We take these pre-judgments of our capacity and value into our lives in ways which are likely to either limit or discourage us, or alternatively can empower us. Consider the dichotomies:

| Limit or Discourage | Empower |

|---|---|

| I am not smart | I am astute and capable |

| People don't like me | Most people respect me |

| I am not good at sports | I have some sporting talent |

| I have limited capabilities | I can learn and improve |

| I will never be successful | If I persist I will succeed |

If the limiting beliefs in the left-hand column are not challenged or tested, these unhelpful beliefs can become so pervasive that they lead to feelings of unhappiness or helplessness.

There is a good reason why the brain guides us towards these negative perceptions of self. They are self-protective. Our survival instinct, particularly our urge for social survival, tries to protect us from any chance of harm. In particular it often discourages us from trying so that we don't fail, deters us from initiating relationships from fear that we may be rejected.

The good news is that there are some strategies we can use to influence our own perceptions. We can question and change our own beliefs and assumptions. When our beliefs limit or inhibit us, we can change them.

3. Understanding Brain and Mind

Brain is the biological foundation of our control system. Mind is our awareness of the brain's activity. We are consciously aware of the activity of our mind. The swift connectivity of our brain operates outside of our awareness.

When the brain is activated, it pursues familiar pathways through its billions of synaptic connections. As a result, choices made by the brain are made quickly because these synaptic pathways easily become habits. The slower processes of the mind allow us to make more considered decisions.

How it Works

These differences between what the brain does and how the mind works are important.

With this information we can easily understand why we sometimes act impulsively and why we find ourselves repeatedly making the same mistakes. The brain's tendency to make a habit out of behaviours that have worked in the past, tends to lead us down familiar paths, even when we don't want to go there. To make a change and respond differently requires the construction of alternative synaptic pathways.

Our slower, more reflective, thinking can modify the brain's hasty choices - when we are prepared to make the effort. As everyone who has changed a habit can attest, this is challenging mental work. The process of change takes time. To change a habit we don't want, we first have to identify a way of acting and thinking that we would prefer. Then we have to practise it until it becomes a new habit. Deliberate practise changes the brain, eventually leading to the establishment of new synaptic pathways and a new habit.

Why it Matters

This explains why it is so difficult to just stop a habitual behaviour. With nothing to replace it with our brain will keep activating the same old words or actions or feelings when a familiar situation occurs. Constructing a replacement behaviour and learning it makes changing a habit more likely.

It is common to feel frustrated when we realise that we have a habit that is not helping us.

Whether we want to stop smoking, stop avoiding exercise, stop procrastinating or control our negative self-talk, there is always a 5-step process for changing a habit.

When we want to stop anything that we do automatically we:

- First have to name the habit and accept that it is harming us.

- Identify the circumstances, people or settings that generate the habit.

- Find a replacement behaviour, something that you can do instead. It is much easier to change a behaviour than eliminate it.

- Visualise yourself using the replacement behaviour.

- Practice using the replacement behaviour until it becomes the new habit.

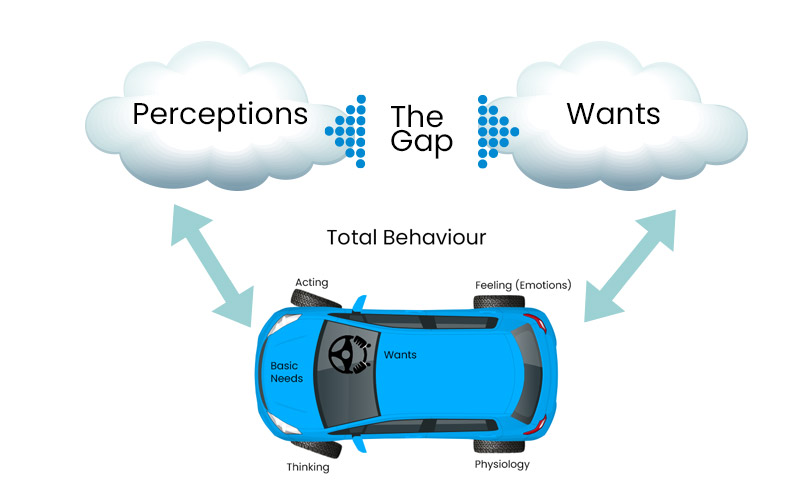

4. What are we comparing when we choose?

Making a comparison is central to the internal choices we make. From moment to moment, we compare what we perceive as our present situation to our ideal: to what we would like to be happening. When there is a gap between what we presently perceive and what we would prefer, we choose a behaviour that we intend will close the gap.

The 'ideal' element of this polarity is self-constructed by the ways we have found to successfully gratify our genetic needs.

How it Works

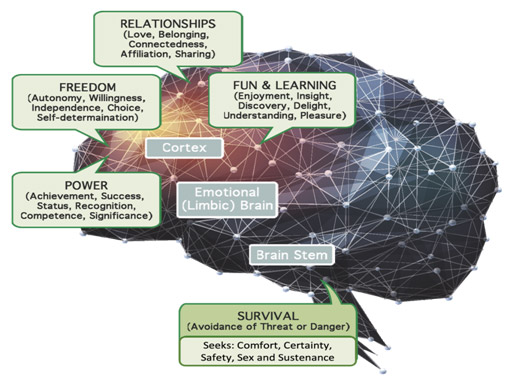

4.1 We have genetic needs.

4.2 Needs conceive wants – the content of our ideal or quality world.

4.3 We compare what we want with our perceptions of reality.

4.1

We have needs built into our genetic heritage. Unlike more primitive creatures, humankind is not born with a preponderance of imprinted behaviours. We are designed to learn - to gradually (and sometimes painfully) acquire the capabilities that we need to survive and thrive. We are constantly presented with choices about how to construct ourselves and how to make our way in the world.

However, we do have very powerful and enduring genetic prescriptions of our own. These enduring directives, our genetic needs,are far more flexible than the exact programs inherited by simpler creatures. Because our needs are not tied to specific behaviours, we have many ways to satisfy them. We don't choose our needs. We do choose how to gratify them.

The Human Needs

We share with all creatures a need to survive – the universal directive that applies to all life forms. Apart from that, our other genetic commands are psychological: they enable us to build capabilities that surpass those of every other creature, and we continue to add to these capabilities throughout our lives – when we choose to.

There are several versions of this catalogue of genetic necessities. Psychiatrists William Glasser and Abraham Maslow, Researchers Edward Deci and Richard Ryan, Holocaust survivor Victor Frankl, and authors Martin Seligman and Daniel Pink each present their own variations. I will present what I believe can be described as the consensus between their views.

We all have genetic needs for:

Belonging (love, relatedness, connectedness, personal association).

Success (power, achievement, status, to feel in control).

Freedom (autonomy, self-determination, free will).

Survival (safety, certainty, nutrition, reproduction, and rest).

As you can see, there are lots of similarities and a few differences between the ways in which the needs are identified. For us, how we name the needs is not as important as knowing that we have them. In turn, knowing that we have genetic needs is of less significance than how we choose to satisfy them.

Because gratifying or satisfying these needs is a source of pleasure, we are motivated to find ways of enhancing our well-being through the promise of these pleasurable feelings. From the moment of our birth, we discover ways to experience this pleasure and we are accomplished archivists of these experiences. When we have discovered that something is need-satisfying, we try to repeat or approximate it (or find an even better experience to replace it). Because we all find different ways in which to satisfy our needs, we discover personally specific experiences, people or events that elicit this pleasure. These personally need-satisfying (or 'quality') experiences provide reference points for us as we seek contentment and happiness. They provide 'the ideal' with which we compare 'the real'. They form the positive pole of the gap that we are always attempting to narrow.

4.2 Needs Conceive 'Wants'

Whatever the needs are named, these genetic drivers underpin the 'wants' that we experience. Our 'wants' are personal avenues of need-satisfaction: the quality moments, people and ideas that become the markers against which we compare our present perceptions. The pleasure that we feel from those experiences arises from the satisfaction of one or several needs.

Striving for need-satisfaction may be a common feature of being human. The way in which we satisfy the needs is individual. Each of us stores in our memory all the experiences, events, activities, people, and places that have been need satisfying. These form the composition of our ideal world or quality world. Our ordinary motivation arises from the juxtaposition of our perception of what is happening right now with a related aspect of our ideal world.

Because they are commissioned by our genes (the biological fragments of human heredity) our needs cannot be ignored. When a need is being satisfied we don't notice it much and it plays little part in our day-to-day motivation. However, when a need is unsatisfied, the Gap between the real and the ideal becomes intrusive. The 'ideal' in our heads increasingly throws up 'wants' that are related to the need that is being denied.

4.3 The Gap: we compare what we want with our perceptions of reality.

The experience of the Gap, the space between what we perceive to be happening and one of our related wants, is the source of human motivation. These perceptions and wants are usually specific to the moment. My motive is rarely a generic 'gap' because things are no perfect. It is usually a specific perception compared to a specific want. I am stuck in my office on a beautiful day, and I compare that experience to my memory of a day in the sun with someone I love, and my feeling is discontent. Or, I have been working hard to win appreciation from a colleague or family member and my efforts are not even noticed. My feeling of being ignored compared to my recall of what it is like to feel deeply appreciated creates a painful 'gap' between what I want and what I yearn for.

All of life is like this. We are urged to behave in ways that we hope (or expect) will close the gap between the perceived present and the preferred want. Sometime the gaps are slight, just a nudge. At other times they are significant and give us a mighty shove. However, whether the gap is big or small, closing the gap (or evading pain) is the structure of our motivation. Comparing the real and the ideal is the comparison that presents us with choices.

Why it Matters

It matters because managing the gap between what we are experiencing a 'real' and the ideal we would prefer is the inevitable background of our lives. Whoever we are and whatever we are doing, this comparison between 'how things are' and 'how we would like them to be' is an abiding constant. Although we are not always aware of it, the Gap is ever-present.

The Gap is the paradoxical source of our motivation and the facilitator of personal growth. Nevertheless, attitudes and beliefs about this difference between the reality of life and the idyll we desire vary widely. Some of us just accept that it is 'just what is'. We say to ourselves something like: “Life was never meant to be perfect” and manage our circumstances through the best choices we can make. The Gap is always there, but because we expect it, we accept it. Because we accept it, we learn to manage it.

However, many people are ever conscious of this space between the real and the wanted. They resent it. They come to believe that life is unfair; that their circumstances are somehow cheating them out of the state of contentment that they feel they deserve. However small the divide between the quality of life they yearn for, and their perception of how things are, they notice it. Awareness of the Gap becomes pervasive. It's easy to become more than a little miserable if you experience life like that!

Because of the Gap, choosing is the ubiquitous activity of the mind. Comparing our present circumstances with our preferred ideal - and selecting a response - is our constant companion as we weave our pathway through life. We are shaped by the choices we make as we respond to the Gap.

Who we are now, and the life we presently lead, are largely the consequence of choices made at some time in the past. Although genetics and circumstances play a role in moulding our life's journey, we are all shaped by the options we take in the face of the events and experiences that we encounter.

In the same way, who we will become, and the degree of well-being and freedom we will experience in the future, will be the result of choices we make now and in times ahead. The Gap may be our burden, but it also emancipates us. Because we always have choices, and will always need to make choices, our choices matter!

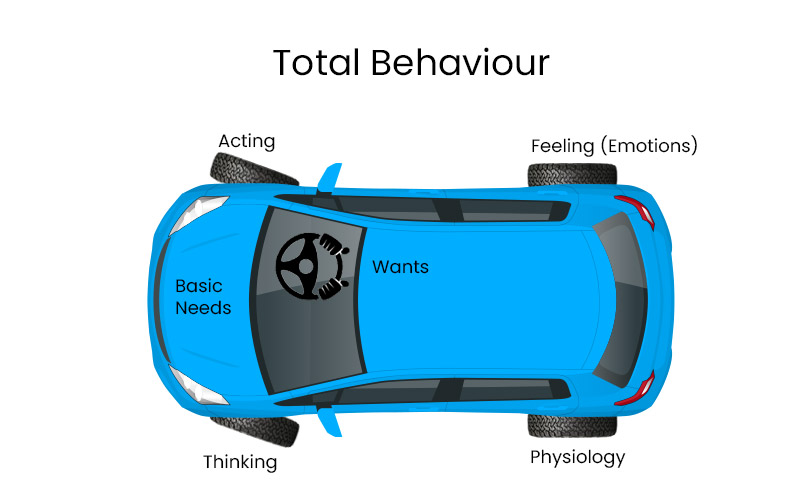

5. Behaving – the way we work in the external world.

Our own behaviours are the practical tools we can apply to bring our perceptions and our wants closer together. We use the generic word 'behaviour' to describe the things we can do that appear to us to have an effect on the real world. We behave in order to make things better for ourselves.

We may be internally controlled, but our perceptions of the world around us, provide the context of our lives. Our behaviours are like the output of our internal processing. We may not be able to control other people or events directly, but we can control ourselves and our behaviours and try to employ behaviours which influence other people and make a difference to situations. Our behaviours are initiated inside us, but they can have an affect on the people and situations around us.

How it Works

When we are behaving, we are doing many things that are predicated by our existence as a human organism. We cannot not behave! To be human and alive is to be immersed in an unremitting procession of behaviours that extends through time and space, marking the passage of our mortality. At any time in our lives, we may be talking, listening, thinking, acting, feeling, running, walking, sitting, sleeping, enjoying, fearing, aching, tensing, relaxing … the catalogue of the ways in which we may be behaving is long and varied. We are always behaving, and every behaviour involves the coordinated experience of thought and action, physiology, and emotion.

The Four Elements of Behaviour

Whatever we are doing to create an 'output' initiated by our brain will always have four components: there will always be action and thought, feelings and a physiological state.

William Glasser used the expression 'total behaviour' to describe the simultaneous occurrence of these four elements of every behaviour: thought, action, physiology, and emotion. He used the very practical metaphor of the wheels of a car to illustrate the relationship between the four elements of behaviour, noting that we commonly have a high degree of control over our actions and thoughts (the front wheels), but only indirect control over our feelings and physiology (the back wheels). Indirectly, we can change our feelings with different thinking, and change our physiology through actions; but very few of us can change the 'back wheels' by an act of will alone.

Why it Matters

Whether our control is direct or indirect, our ability to manage and change our behaviours is intrinsic to the effectiveness of the four 'wheels' of our behavioural system. Because they occur concurrently, changing any one element of our behaviour changes them all. If we change our actions, our feelings, thoughts, and physiology will match the new action.

This interplay of our behavioural options helps us to steer our lives. Each of the components of our behavioural 'car' is different, but each is yoked to the others by neurological necessity. Knowing this offers us far greater consciousness of control than we would otherwise seem to have. When any one of the elements of behaviour is not helping us to narrow the Gap, we can choose to focus on a different one. By changing our thinking we can initiate new actions: take actions that will alter our thoughts and feelings; or shift to a more alert physiology by noticing the urgency of our tasks.

Without this interplay of the elements of behaviour we would lack the flexibility which makes humans so adaptable. We are able to manage obsessive thoughts, immobilising feelings, and ineffective action by activating a different element of behaviour. Actors on the stage of life, we can attend to the reaction of the 'audiences' to whom we play, and then change our acting to elicit the response we seek. When they are needed, shifts in our thinking can transport us to a different perspective, or focus our attention on another of our many wants.

Even though we have this capability to change our behavioural 'wheels', this control is not automatic. We have to learn to take advantage of this behavioural flexibility and engage the determination in order to activate this potential. It is alarmingly easy to get stuck - to repeat an action we know is not working long after it is not helping us. That's the nature of the brain. Because our neural learning automates our behaviours, we often keep using behaviours that are not useful to us. As we have noted, we can change these habits of mind - but not easily. The grooves in the cerebral sand often run deep, trapping us in the habits we have constructed even when we don't like where they are taking us.

Remember, almost all of our vast repertoire of behaviours is embedded in automated patterns that we initiate and execute without conscious thought. The brain runs our lives by doing what it has always done. To distract it from its habitual repertoire requires a conscious nudge and a commitment to learn and use new pathways.

So it's commonplace to keep doing things that don't work for us, or that even prolong our discontent. The 'habit brain' can persist with learned behaviours even when they are of no use to us. The human capacity for spinning the wheels in a familiar rut is ever-present, but not helpful.

However, we can change our 'state' - our total behaviour - when we harness our mind's ability to alter the course of our brain's activity. The behavioural system's capacity for adaptability is there to help us. The four wheels of our behaviour car provide alternatives, so long as we pay attention to them and expend the effort required to change. To utilise our potentially immense suite of behaviours we have to pay mindful attention to what is happening to us in the present moment.

We can, when we choose, respond mindfully to the Gap. We can identify and abandon unhelpful thinking, acting, feeling or physiology and change our actions or thoughts to those that offer greaterneed-satisfaction. Whatever 'state' we are experiencing, our ability to observe ourselves in that state and to change our thoughts and commence different actions is always present.

6. How to steer your life with a process based on Choice Theory.

From the Choice Theory explanation of how the mind works, we can easily derive a way of talking to ourselves and others to help us get more of what we want and less of what we would rather avoid.

The key components of the Choice Theory explanation are our perceptions, our wants, and our behaviours – and of course the Gap between our perceptions and our wants.

When what we perceive is not what we want, we can choose a behaviour that we believe will change things. This is the very simplest form of 'how we manage our lives.

We can put this into simple coaching questions that look like this:

- What is happening?

- What do you want?

- Is what you are doing getting you what you want?

- If not, what else can you do?

Let's call these the Reality Thinking Questions.

How it Works

The use of these procedures comes from what William Glasser called Reality Therapy (though he developed the therapy before he described Choice Theory). From this therapeutic process we can use these procedures in many different ways.

- As counselling questions (As William Glasser did)

- As Coaching questions

- As personal reflective questions

- As problem solving questions

We can apply them to individuals or groups or teams.

Sometime described as 'the procedures that lead to change' these questions can be presented in a more sophisticated way, such as in the WDEOP formulation illustrated below.

This formulation is designed to emphasise that the key question - IS IT WORKING - is the crux of the process.

Why it Matters

If we were resourceful in every situation, if we responded to all of life changes in a reflective and useful way we would not need these procedures. However, we easily get stuck.

Which behaviour to choose in a situation where we are not getting what we want (and it is painful to us) is not always apparent. Because our behaviours easily become habits, we often repeat the same behaviours over and over again with the same unhelpful results. Or we find ourselves trying to influence people or events without the clear thinking that we need to make the difference we want to make.

In these situations, in any situations in which we want to steer our lives more effectively, the Reality Thinking questions can help us to manage ourselves and choose the most useful behaviours available to us.

(You can go to the procedures that lead to change on this website for more detail)