Free Resources

Free Resources

Leadership by Design

9 Leadership Insights from Human Design

Effective leadership behaviour deliberately adopts strategies and practices that are aligned with the operations of the human mind. It makes sense! Why would leaders engage in a struggle to be effective when we can design our leadership practices from these 9truths about how the mind works:

We are designed for internal control

We have genetic needs

We are all motivated by 'the Gap' between the real and the ideal

The human brain is alert to biological and socail threat

Compliance is never enough

Leadership power is paradoxical

First lead yourself

Human Systems

Leadership Effectiveness

1

We are designed for internal control

Everyone is internally controlled. We are sealed inside a bag of skin that can take in information from outside itself but has its own control system: a vast number of binary switches that we call the brain and the consciousness that emanates from the brain's energy – which we call mind.

Because everyone's control system is inside them, we can't motivate or influence people from the outside. When we are leading, we are doing our best to provide influential information for the consideration of other people's minds.

Attempting to 'make people do things' activates the brain's self-protective mechanisms, which lead to resistance. Both the survival instincts and the need to be autonomous push back against any attempt to coerce other people.

The secret of effective leadership is to persuade other people to do what you want them to do because they want to do it.

We can of course encourage people. The relationship between us may be strong enough so that they want to work with us and seek our approval. If we are trusted they may be inspired by our example or by our ideas. We may be able to arrange events and circumstances so that other people are influenced in a way that suits us. They may see us as a stepping-stone to something they want. These things are possible.

But the choices about the behaviour of anyone who is not us, is made by them!.

Whether we are leaders of our children, leaders of our school or business, or leaders within our community, this truth is always with us. We provide information from the outside of the people we need. As leaders, all we can control is the information we impart to others,and the way we communicate that information.

This first reality leads to the second:

Each mind is a self-organising entity that is designed to aid us in reducing the gap between what we perceive and what we want. Narrowing that gap is what motivates us.

2

We have genetic needs

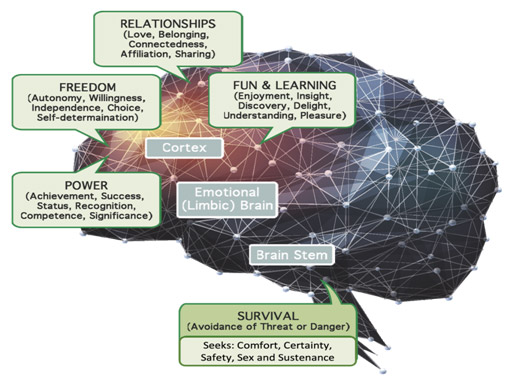

Although humans on not have specific behaviour imprinted in their genes, we are born with genetic needs. This mean that, although we are born helpless we are relentlessly driven to learn how to satisfy these needs. The needs are named slightly differently by various scientists and theoreticians, but they are basically in 5 groups as illustrated below:

The most primitive part of our brain manages our need for survival. The cognitive brain urges us satisfy our cognitive needs.

Because we all have these needs, and our brain urges us to satisfy them, every human behaves in ways that will lead to the satisfaction of these needs OR to avoid the pain of the needs not being met.

The pleasurable or utopian circumstances (which we are constantly pursuing) provides our motivation. Although we all have slightly different conceptions of the ideal, we are all trying to pursue the satisfaction of our needs:

- By striving to be more capable. Therefore leaders who recognise our strengths and give us opportunities to grow in capacity are likely to influence us.

- By preferring to do things willingly, so leaders who avoid coercion and encourage personal autonomy will encourage us.

- By enjoying a workplace in which satisfying relationships and supportive communication are embedded in the workplace culture.

- By offering opportunities to learn and have fun at work. Notice that learning that feels growthful is need satisfying, while learning that addresses perceived deficits can seem threatening.

- And of course, by ensuring that everyone is safe at work.

3

Everyone lives in their own motivation gap

We all live in 'the Gap' between how things are in reality and how we wish they could be. It's like a backdrop against which we make choices in life. We all constantly compare our current situation with our ideal one, whether we realize it or not.

Every day, we try to make choices that will bring us closer to our ideal life. We want to feel in control and minimize discomfort, so we make decisions to promote our well-being or to avoid pain and suffering. It's rare for anyone to feel completely satisfied because the Gap is a natural part of being human.

Whether our Gap is big or small, we're always striving to make the best of our lives.

Our motivation comes from this Gap. We are always comparing our present experiences with how we want things to be and acting to reduce the difference. Our brains are always seeking ways to adjust the Gap and protect us. We make choices consciously or unconsciously, trying to bring our experiences closer to our personal ideal of how things should be.

Notice that all these choices are personal. My ideal is not your ideal and our present experiences of the moment are always individual. This unsurprising truth provided two challenges for every leader:

- The importance of being thoughtful about what is happening in the minds of the people that you lead. We should never assume that the gap that is motivating us is important to them. When we sense resistance, there is always a reason.

- The more we can do to co-construct our work goals and the purpose of our work, the greater the chance that we will bring our 'gaps' into alignment.

4

The human brain is alert to threat and danger!

It is well-known that the most primitive parts of the human brain are designed to alert us to threat. More recently, neuroscientists have shown us that, because we are social creatures, we are as alert to threats to our social survival as to threats to our physical survival.

When threatened we tend to behave in ways that avoid the potential pain, which is in stark contrast to the need-satisfying motivation described in the previous section.

People are less efficient and effective when they feel threatened. Our emotional brain sends the signals that release adrenalin, cortisol, and similar chemicals which ready us for defence or attack but interfere with clear thinking.

Effective leaders try to avoid activating these social threats in the perception of the people they work with. Specifically they:

- Avoid threats to the status or sense of competence of their staff and provide encouragement and respect for the ability of workers.

- Avoid confusion or uncertainty by communicating a clear vision and by being predictable and trustworthy.

- Provide good reasons for their expectations and encourage as much autonomy as possible so that everyone works willingly rather than feeling coerced.

- Developing good relationships with their staff and encouraging collaboration and supportive communication in the workplace.

- Makes every effort to be fair and even-handed and avoid favouritism in their treatment of the workforce.

5

Compliance will never be enough

Although leaders often wish that their employees would 'do as they are told', simple compliance is never enough. Compliance is a very low level of productivity.

Consider the eight levels of commitment illustrated below.

Few of us would be satisfied if our workforce was apathetic or resistant. But would we settle for 'compliance' (performing at the minimum acceptable level)? Would we be happy with our staff if they simply conformed to the workplace norms?

Most of us would be very happy with a hardworking and responsible workforce, with a staff that felt they were personally accountable for the outcomes the business is striving for. So much the better if they demonstrated creativity and enterprise in their efforts to achieve the success and productivity of the organisation.

However, in striving for the higher levels of commitment and accountability, it is crucial to recognise that compliance is NOT a step towards responsibility and contribution, it is the opposite. When leaders attempt to force compliance, even if they are successful, the cost is huge. Attempting to force compliance creates resistance by pushing against three features of human genetic biology.

Humans have a need to be autonomous. The preference for doing things willingly and resisting coercion is embedded in the human gene.

Each individual has a need to be significant, to be personally effective and recognised as such. Coercion diminishes us and leaves us feeling powerless if we comply.

Into our need for survival is built the tendency to push back against the invasion of another person's will. When we attempt coercion, our survival system initiates a self-protective response. If we do comply we withdraw our energy. If we remain energised. We use our energy to resist.

6

The Paradox of leadership power

True recognition of the limitations of leadership is, I believe, the key to unleashing the power of the leader's most potent asset – his or her ability to manage self in order to encourage, inspire and empower other people.

Whether we recognise it and accept it or spend our working life railing against it (and some do!), all leaders are largely dependent for their effectiveness on the performance of other people in their organisation.

As leaders who want to experience success, embracing this paradox is more than important - it is pivotal!

Unless we can achieve the results or productivity we strive to create on our own (and we can't), then dependence on the skills, abilities and gifts of others is a 'given'. It's the people we lead who create the products and ensure the effectiveness of every organisation.

This element of dependence, this inconvenient 'law of reliance'2, is the actuality and the paradox at the heart of leadership.

For many of us, this comes as an unpleasant revelation. It's confronting that at that point in our careers when we seem to have been vested with significant authority, we discover that our ability to be in command is an illusion. A prized external measure of our personal capability - the elevation in our status to a leadership role - turns out to be far different from our expectation. The assumption that position power would be associated with increased control over people and events turns out to be a mirage!

In the world of authentic experience, this uncomfortable reality soon becomes apparent. We accept responsibility for the quality and productivity of other people's work, and with this comes the obligation we feel to deliver meritorious outcomes. But we soon realise that we have little direct control of what our staff do to achieve results.

The frustrations that go with this realisation are commonplace – and understandable. It seems unreasonable for anyone in a position of responsibility to be relatively powerless – dependent on their subordinates for success. It seems like a formula for creating discontent!

However, most of us soon learn that expressing our frustration by increasing our efforts to control and manipulate our team members only takes us deeper into the contradiction.

This is where the second element of the paradox at the heart of the leader's challenge kicks in.

People can never be made to do what we want them to do.

Remember: everyone is internally controlled. Of course, up to a point, we can use our position power to insist on their compliance – or at least the appearance of it. Often our colleagues are not so bold as to challenge us directly. If we put our foot down and insist on obedience, then our staff will usually go along with us to keep their jobs or to keep the peace. In public, our position power may result in acquiescence, and any resistance will become passive. However, compliance comes with a corresponding decrease in the creative engagement of our staff.

The problem is that trying to control the behaviour of other people by overpowering them actually creates resistance. Coercion can never tap into the wellsprings of human motivation or encourage high quality work and commitment. The under-appreciated biological law that emerges in human behaviour is written starkly in the annals of history:

If you push me, I will push back!

7

First Lead Yourself

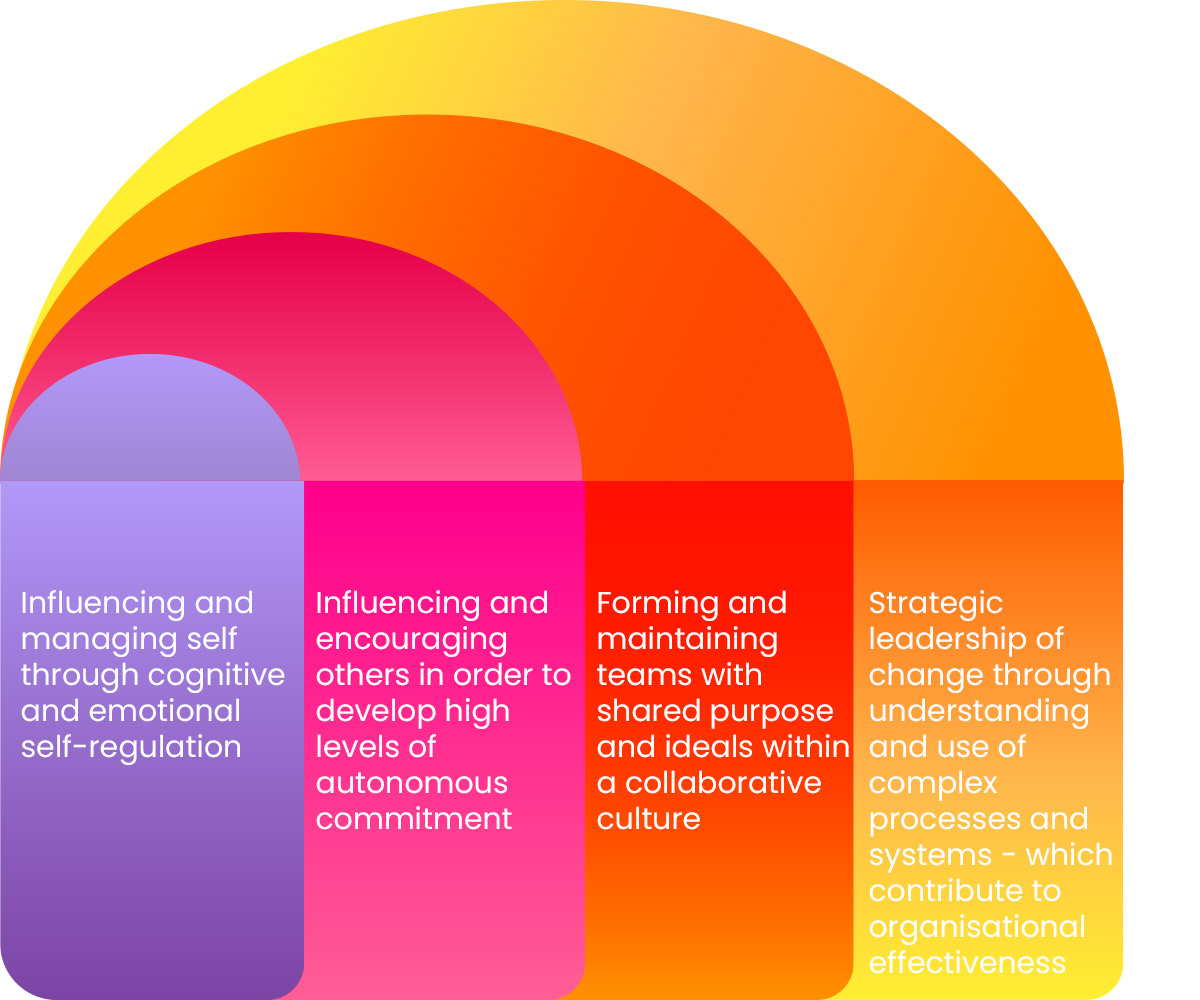

The FutureShape Leadership Framework

It follows from the above, that before we can lead anyone else well, we need to lead and manage ourselves.

The leadership framework I teach, and use, makes that clear.

Because all we can do is provide information to other people: through what we do and what we say, and through the way that we do it or say it, self-management is always the origin of our leadership influence. Only when we manage ourselves well can we influence and empower other people.

The coherence and clarity of our communication with those we lead comes from our ability to manage all of the aspects of our own behaviour.

When we control our own outputs well we can be deliberate and responsive in providing the information and inspiration that will influence the choices of others. If we are trustworthy, we will become trusted.

If we get this right, we are then in a position to be a positive influence on the thoughts and actions of the people we lead. We can then work with our people (be that our colleagues, our family, or our community) to form effective groups and teams to create systems and processes that will optimise our work together.

8

Human Systems

Its easy to believe that the artificial systems that we create in order to maintain order and seek progress in our organisations actually describe how the world works – at last in the world of work!. All those hierarchies that seem to describe differential status; the org charts that are created to describe who has the right to give orders to whom, the little boxes and arrows drawn on a page to describe supposed lines of communication. If they were real they would create a workforce of cowed, compliant employees, puppets dancing to the tune of a bureaucratic machine.

Actually, the real world is not like that. The real world that we inhabit is biological and neurological, it is made up of relationships and connections. The basic building blocks of life, the smallest sub-atomic particles that mankind has discovered, do not exist except in relationship to each other. It is through relationships, in the way that minute particles attract and respond to each other, that life is created and sustained.

In the same way the vitality of every organisation is constructed by the relationships between the human organisms, the people, who work together there. What energises and motivates us are not black boxes drawn on a white page, but the relationships within which individuals are liberated to be their creative selves. Our biology, our genetic inclinations to be personal significant and autonomous in the context of relationships with each other, is the wellspring of human effectiveness.

In teams, networks, and communities of practices, individuals connect and respond to each in a dance of mutual influence. Through collaboration and conversations people share and learn, becoming more agile and capable together than they are when working alone. When leaders invest the time and energy to be trusted they become influential, then the relationships they enjoy with their staff are the foundation of their effectiveness in working together.

It is not that the systems that we employ to bring order are of no use. They do create a sense of order and provide efficiencies that jostle with our natural tendencies to be independent and self-focused. However, the usefulness of these systems is limited. When organisations depend on them they do not have the energy to sustain themselves. They spiral toward entropy.

As leaders we are best served by seeing our organisation as a mirror of the biology of each of its human constituents. When we do this we encourage the circles of personal influence, the natural attractions and enthusiasms that motivate and energise, to engage and direct our efforts. The leader who nurtures the relationships that emerge spontaneously and the synergies that bring minds together in action, is using the rather than defying the naturally emerging forces of the relational world.

9

Leadership Effectiveness 1

Which leads to the need for leaders to understand what they can do and what they can't do to be effective in their work. As Peter Drucker observed, effectiveness is the test of leadership. Are we able to lead other people in ways that enable our team or organisation to achieve their intended purpose?

There are 4 dimensions of leadership effectiveness.

In my book 'The Leader-Mind Equation" I express it as an equation.

E = C + D + C - D

The first C is capability. Every leader is stranded without capability and the productivity of every school, business, club, family, or community is improved when capability is enhanced - and diminished when it is eroded. Leaders build capability by teaching, coaching, mentoring, providing learning opportunities and encouraging development. Capability does not have a ceiling imposed by position and present status.

"Effective Leaders leave a trail of capability in their wake."

Putting energy into building and sustaining teams grows capability growth. Encouraging individuals to stretch their knowledge and skills grows capability. Modelling relational leadership AND being explicit about what you are doing grows capability. Offering skill-based learning and leadership learning grows capability. Encouraging experimentation and providing a soft landing when things don't work out grows capability.

Mandating attendance at learning events doe NOT grow capability. Putting pressure on people to learn or change does not grow capability. The work of Edgar Schein on learning cultures shows clearly that the kind of learning that is 'keep up or you will fall behind' adds to individual stress and discourages self-generated learning. Encouragement, support, modelling, and opportunity are the keys to building capability.

The + D is clear direction. People work most effectively when the WHY is clear and the purpose is shared. Creating this clarity about where the enterprise is headed and how success will be measured is a beginning. Teasing out shared beliefs about how success is to be achieved, and describing the values required of an effective culture, completes the picture.

These are the four frames of the 'Window of Certainty'2

When a leader takes the time to collaboratively agree the purpose, outcomes, beliefs and values they all share, the organisation thrives.

- Vision and Purpose show everyone where they are going.

- Outcomes provide an agreed measure of their progress.

- Beliefs about how to achieve the outcomes lead to strategies that are aligned with each other.

- Shared values create a cohesive community.

Creating this common direction and shared outlook among the individuals, teams, and communities of practice in the organisation enables everyone to work creatively and autonomously while still aligned with the direction of the organisation.

The second + C is commitment. To be deeply committed to their work, employees have to be deeply engaged and enthusiastic about what they do and the context in which they do it. Motivation is the key to this, and because we are internally motivated employee commitment can be summed up by the phrase:

What we do willingly, we do well.

Deci and Ryan focus their research on the consequences of the genetic need for autonomy. When we feel in control of our own lives: when we are self-determined, free from imposed constraints and free to make independent choices, we tend to thrive. When we contribute willingly, our own powerful intrinsic motivation is the driver of our behaviours. This research ties personal freedom strongly to well-being. When we are willing,we feel well.

On the other hand, when we feel controlled by others: when we are limited or constrained, when our options are limited or when we are behaving unwillingly, then our drive and sense of purpose is weak. Imposed limitations tend to cultivate lethargy.

Now I am not suggesting (and nor are Deci and his colleagues)that the solution is for the staff to do whatever they want. That would be anarchy, an avenue of constant uncertainty. Every person at work knows that, even in the best of jobs, there are some tedious or unpleasant tasks that just have to be performed. However, the research of the Self-DeterminationTheory community shows us that workers are likely to be committed if the work context and culture generally encourage:

- Meaningful work.

- Opportunities for personal achievement.

- Individual choices about how to achieve work goals.

- Freedom from excessive supervision.

- Scope to make inputs into how work is organised and performed.

- Personal creativity and initiative.

It's when the volume of imposition becomes pervasive that we turn off our commitment to work.

We can link commitment to the genetic needs we explored in section 2. Need satisfying work is the most likely to gain our commitment. When work is meaningful, when the workplace is safe, when it supports personal and team achievement, when there is mutual trust and satisfying relationships, when personal autonomy is encouraged and respected them the people who work there will be committed and engaged.

Creating a need satisfying workplace is not so much what leaders do as what they encourage and allow. Because humans are internally controlled, they are driven to satisfy their own needs. The leader's job is to invite the staff into respectful dialogue so that they can be co-creators of a workplace that liberates the staff to satisfy their own needs in a responsible way.

The last element of the equation is - D. Minimise distractions.

To make sure that the main thing is always the main thing, that the clear direction and purpose of the business is always the first priority, the job of the leader is to minimize distraction.

Distraction in any organisation comes in many forms. To name but a few:

- Work that does not need to be done.

- Meeting that do not lead to outcomes.

- Too much bureaucratic oversight.

- Leaders pursuing their own agenda.

- The intrusion of unresolved conflicts.

- Blaming and complaining when things go wrong.

- Self-protective behaviour that hides or minimises problems.

- Discouraging employees from 'speaking truth to power'.

- The culture in practice is not the one that is espoused.

- What we say is not what we do.

These not only sap energy and confuses priorities but can often contradict the beliefs that are part of the 'Window of Certainty' of the institution.

If leaders communicate clearly that distractions are unwelcome, help their staff to identify interference when they perceive it, and make it a priority to minimise these distractions then everyone is freed to concentrate on the effective work that leads to important outcomes.

Summary

'Leadership by Design' makes sense. Attempting to lead and manage other people by pushing against the realities of human design inevitably leads to frustration.

There is no longer any mystery about the core drivers of human behaviour. The reasons why people resist coercion and work lethargically in the face of external control are well known.

Similarly, the behaviours and strategies that engage and energise the human mind are also well known. By recognising important features of human design we can liberate trust, commitment and responsible behaviours.

Leadership by Design makes sense.

Sources and References

1 Rob Stones: 'The Leader-Mind Equation' 2020.

2 Rob Stones and Judy Hatswell: 'The Window of Certainty' 2016