Free Resources

Free Resources

Teaching Students to Manage Themselves

Based on my new book: 'Teaching Students to Self-manage in the Classroom – Strategies that Promote Wellbeing and Resilience’.

What is a self-managing classroom?

- A self-managing classroom is one in which everyone in the room, including the teacher, manages their own behaviour responsibly.

- In such a classroom being responsible is defined as 'getting what you need to learn and thrive without interfering with the ability of others to get their needs met'.

- In a self-managing classroom, students are expected to manage their own behaviour and learning. It is the teacher's job to teach them how, and show students how to do this, and to remind them with thought- provoking questions when they seem not to be managing themselves responsibly.

- It is everyone's job to develop positive relationships with every member of the class and to be well aware of which behaviours improve relationships and which damages them.

- In a self-managing classroom, students are taught enough about the psychology of human behaviour, at an age-appropriate level, so that they understand themselves and others. They use this knowledge to work collaboratively with their classmates and the teacher and to be supportive of their peers and their teacher.

- In a self-managing classroom, the purpose of student self-management is to enable students to take responsibility for their work and achievements. There is no artificial separation of student learning from student behaviour. Students self-manage and self-evaluate their own performance in order to demonstrate quality in all aspects of their schooling.

- A self-managing classroom is a happy and need-satisfying place. Students and the teacher look forward to coming to school every day.

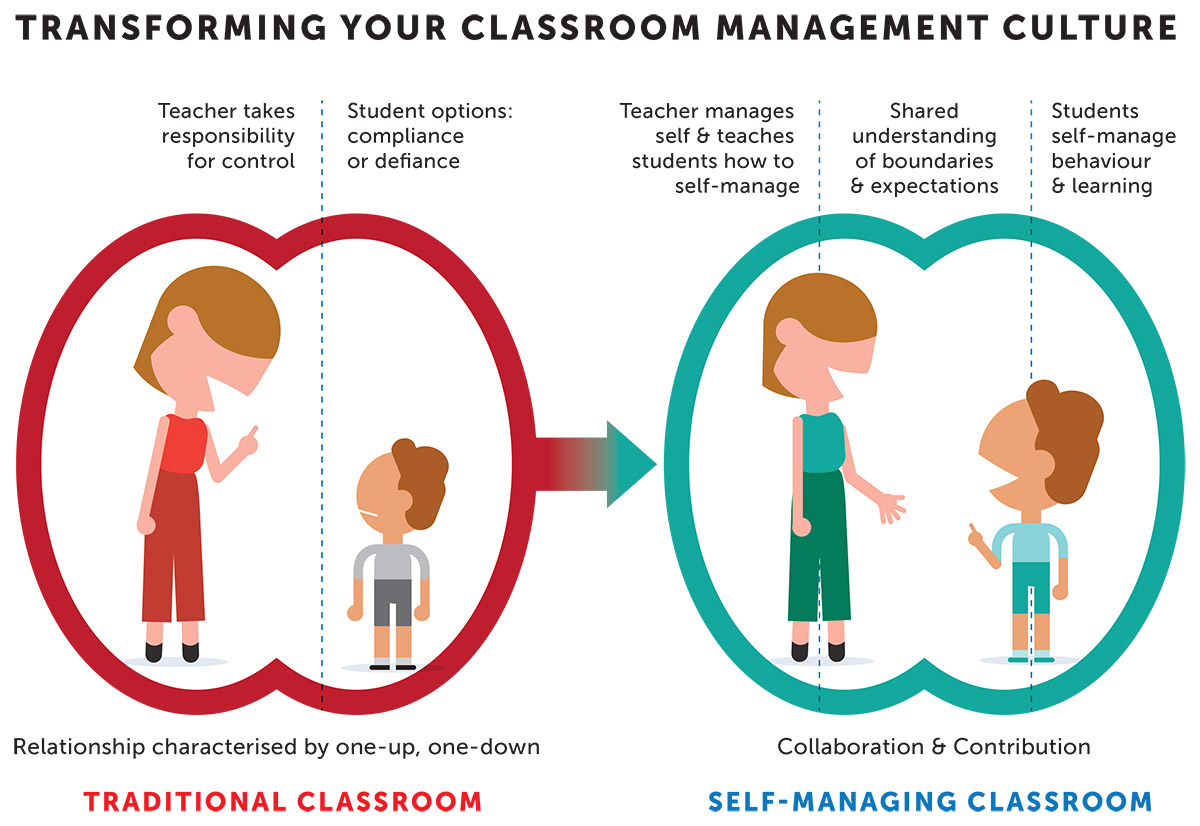

The self-managing classroom stands in stark contrast with the traditional teacher-managed classroom in which it is the job of the teacher, not the students, to manage the behaviour and learning of the student.

Why is traditional classroom management so difficult?

A common assumption that underpins the 'traditional' way of managing in the classroom is that students must be controlled before they can be taught. This intuitive assumption is understandable. Students who are not managing themselves responsibly, do have a damaging effect on teaching and learning effectiveness. Therefore, it is argued, students must be controlled before they can learn!

However, the solution then becomes the problem – or rather the problems.

Because teachers take responsibility for the management of students, many students do not learn to take responsibility for themselves.

When students are controlled by their teachers, they are faced with the same choice as adults who are subject to coercion: compliance or defiance.

Both compliance and resistance have long-term negative consequences. Children who are compliant in the face of coercion are in danger of developing an external locus of control and may always rely on other people's opinions and evaluation, compromising their own independence.

Children who choose defiance are often denying themselves opportunities for learning and growth. Defiance also has a very painful short-term consequence as well: defiant students are set up for an arm wrestle with their teacher which is painful for both.

When there is a conflict of this sort between student and teacher, the school is organised to make sure that teachers win! So teachers are usually vested with the power to call on even more painfully coercive practices (most of us can write a list). The catch-22 is that the more coercive the school's student management practices, the more likely it is that children will respond badly by 'playing up' or 'switching off' in class.

The use of coercion makes conflict in the classroom inevitable. One of my former colleagues explained the inevitability of the negative outcomes of teacher control like this: it's biology stupid! Humans are neurologically designed to be autonomous and resist coercion – so that's what they do!

Many teachers report that as much as 60% of their time and energy is spent on managing and organising students in their classrooms. This is a huge frustration, but it has another problem effect as well. When I introduce teachers to the strategies in this booklet, they often say "I can't do all this. I don't have enough time". Because they have not taught the students how to self-manage their learning and behaviour it is hard for them to conceive of a classroom where so much time is saved when students take responsibility for learning and behaviour.

How do you make the change:

From teacher control to student self-management?

Teachers who want to work with their class to make this worthwhile change are faced with two main challenges:

- The challenge of habits (their own and those of the students).

- The challenge of expectations (often the expectations of teachers, students, school executives and parents).

These are complicated by the complex nature of the changes they are making. Although there are some powerful steps that teachers can take to begin the shift from controlling students to teaching them to manage themselves there is no magic bullet.

The Teachers Purpose is the shift the locus of control and responsibility:

responsibility |

Students will take responsibility for their own self-management. |

responsibility |

Students will take responsibility for the Quality of their own learning. |

responsibility |

Students will be expected to self-evaluate their behaviour. |

responsibility |

Students will be expected to self-evaluate and manage their own social behaviours. |

Please notice that this is NOT another plan for behaviour management by the teacher. It is a total student self-management plan!

Students are taught to manage and monitor their learning and progress AND their classroom and social behaviours.

How do you make the change:

The issues of unhelpful student behaviour and student perception of failure are inevitably tied together. Failing students quite naturally attempt to satisfy their power needs in inappropriate ways and often disrupt the learning of others.

This means that it is important to use the time and effort saved from student management to create engaging and encouraging pedagogy. This goes hand in hand with teaching students how to manage their own behaviour and learning. Boring and uninspired teaching will not support student self-management.

One of the first principles of a self-managing classroom is the teacher's intention to eliminate failure through bes- practice pedagogy. Although effective teaching is a dynamic process, the practices listed below are likely to encourage and inspire students:

- Supportive and trusting relationships between teacher and student. Students are told explicitly that the teacher is there to help them and wants only the best for them. The teacher uses supportive connecting behaviours.

- When new information is presented, the teacher gives clear explanations of the content and uses repetition and revisiting to help students master the basics of the new material.

- Active learning strategies are employed to involve students in the learning process. This can include discussions, group work, hands-on activities, and problem-solving exercises.

- Clear Learning Objectives are set for each lesson so that students know what they are expected to learn and achieve by the end of the class.

- Engaging Content: Use diverse and engaging teaching materials to capture students' interest and cater to different learning styles.

- Sufficient differentiation to accommodate the diverse learning needs, learning history and abilities of students.

- An emphasis on personal best so that each student is focused on improvement of their previous performance.

- Regular formative assessment to enable students to gauge their own progress and level of understanding. Timely feedback helps students to manage and enhance their performance.

- Reflective self-evaluation and both self and peer assessments that assist students' awareness of the criteria and standards related to each learning task and understand how to improve their work.

- A collaborative culture which encourages open communication between students and teachers. This fosters a supportive learning community where students feel comfortable sharing ideas and asking questions.

- Opportunities for continual Improvement so that students can revisit and improve work that is not the best they can do.

- The teacher shows passion and enthusiasm to inspires and motivate students.

12 practices that encourage the self-managing classroom.

The 12 practices presented below will enable you to make a start in your creation of a self-managing classroom. They are:

Share your intention.

Enhance Positive relationships (connecting and disconnecting)

Tell students what the changes will be - and why.

Use clear but signals to get students attention.

Set clear boundaries.

Define responsible behaviours.

Use 'let's work it out' when things go wrong.

Replace commands with question.

Develop a repertoire of useful questions.

Use assertive practices.

Teach the behaviour car.

Encourage setting personal goals.

For many more ideas, look out for the publication date of my new book: "Teaching Students to Self-manage in the Classroom - Strategies that Promote Wellbeing and Resilience".

The practices for changing from teacher management to student management are not in a strict order, though the first two:

Announcing your intention to end your attempts to manage your students and substitute the teaching of self-management.

And

Eliminating coercive practices.

Must be tackled early on or they will sabotage the other strategies.

These strategies are pragmatic rather than idealistic. It is not my intention to promote weak or ineffective practices based on dreamy conjecture. Quite the opposite is the case. Student achievement is based on the 'discipline' of effective teaching and the promotion of effective learning.

As you read these you will certainly find that you are already using some of the ADOPT behaviours. The challenge is to avoid using the AVOID behaviours while adding more and more of the ADOPT behaviours.

I have tried to accentuate the positive changes that you will make by usually (though not always) putting theADOPT suggestions first.

In the 12 practices that I recommend on this web page, I have used the symbols below to indicate what practices teachers should ADOPT, and what they should AVOID or reduce to facilitate the change from controlling students to teaching them how to self-manage.

1

ADOPT the practice of sharing your intention to teach your students the skills and knowledge they will need to manage themselves.

Explain to the students that managing themselves and their learning is their job. Your job is to teach, demonstrate and steer them through the curriculum.

Also begin to explain to students that you are making this change to encourage higher levels of achievement, greater commitment to learning and increasingly responsible behaviours from and for them as a result of this change. (It is important that you explain the changes that you are implementing. Students will be suspicious if you try to implement them by stealth).

You can set this new paradigm in motion with an activity that illustrates it quite simply:

Ask students to do a simple hand-eye skill such as flipping a counter or coin into the air to above your eye level and catching it on the back of same hand. Demonstrate the skill as part of your explanation.

When all of the students have completed the activity begin a discussion by asking the questions:

- What did I (your teacher) do? [show what to do; ask students to do it].

- Who had to complete the task and 'learn' the skill? [the students had to do that].

- Is there anything that I, as your teacher, could have done to achieve successful completion of the task except showing you what to do, explaining what to do and asking you to do it?

You can follow up by saying: 'That activity tells us something about my job in your successful learning and your job. If you want to achieve your personal best in everything we do, I can't achieve that, only you can do that.

My job is to teach, explain, show you how and encourage you.

Your job is to manage yourself and your own learning.

AVOID any appearance of bossing, managing, or controlling your students. There is a pragmatic and psychologically important reason for giving up your role as controller or manager in the classroom.

Although imposing your own will on students may be partially successful some of the time, it will almost always lead to resistance and resentment. At best you will get compliance from many students, not wholehearted engagement.

Even more importantly, if you manage the students, they will not need to manage themselves. They will go along when they want to and play the game of 'make me' when they don't. Crucially, they will not get any better at managing themselves.

However, this does not mean that the teacher does not have a role in setting boundaries and insisting that students remain within those boundaries. It will always be the teacher's job to be the boundary rider.

2

ADOPT deliberate efforts to create even more positive relationships with all your students and between student and student. When students believe that you care about them, that you respect them and that you are genuinely doing your best to contribute to their well-being, they will trust you. That trust means that even when you are teaching something that they find challenging they will do their best because they know that you will not waste their time or teach something that they are incapable of understanding.

Ensure that your reasons for wanting to strengthen the relationships with them is no mystery Teach the students that there are connecting and disconnecting behaviours and the effect of using these.

Most students already know that there are behaviours that help them to get on well with each other and that will improve their relationship with you. You can use their knowledge and experience to come up with a list that puts this in their own words. You can use the list on the right to help you, but I suggest that you encourage the students to come up with their own ideas, and present these ideas in language that makes sense to them.

Having a clear list of behaviours that will support positive relationships helps you to begin to teach them the habit of self-evaluation. When a student is criticising another member of the class, or making a disparaging comment, or using bullying behaviours, you can ask:

- Will that behaviour improve relationships in this classroom, or make them worse?

- Is that a connecting behaviour or a disconnecting one?

The more that you ask students to self-evaluate their own behaviour, the more likely it is that they will ask themselves these questions. This is far more powerful than reprimanding or correcting students because questions ask for a response from the brain's control centre.

AVOID the use of disconnecting behaviours in your own communication.

In particular, work hard to eliminate these behaviours from your repertoire:

- Punishments

- Threats

- Rewards

All these disconnecting behaviours are experienced as coercive and imply that you have, and will use, superior power. Replace these with connecting behaviours, and with the various 'work it out' strategies presented in this book.

Eliminating threats and punishments is crucial. These practices help you to 'be in control' in the classroom but discourage students from taking responsibility.

Ask students to identify disconnecting behaviours – behaviours that make things worse in the classroom (and home) and be open and honest about your intention to eliminate these behaviours from your own repertoire.

3

ADOPT Tell students what the changes will be and why. Inform students that you are making some changes so that they, rather than you, will be expected to be in charge of their own learning and behaviours. Tell them what you intend to do and why.

Students will notice as soon as you begin to do things differently. One of the most important steps in helping students to self-manage is to always give them information about the purpose of your own behaviours and WHY you are choosing them.

By providing information about WHY actions are chosen and always giving reasons for our own behaviour, we are communicating respect.

When we tell another person WHAT to do and HOW to do it we are establishing a one-up: one-down relationship. We tend not to do that with individuals we respect and value.

Explain WHY you are making these changes and let them know that you will be teaching them everything they need to self-manage themselves.

AVOID telling students WHAT they are to do, and HOW to do it, without giving reasons.

Replace this by explaining WHAT they are to do and WHY it is important for them to be in control of their own behaviour and motivation.

Also explain why you are setting lesson intentions and learning goals and what part these play in the progression of their learning.

Change from using Coercive Practices to manage students to Assertive or Authoritative Practices to encourage self-management (see notes on next page).

4

ADOPT

The use of clear signals to get the student's attention. These signals should not require you to overpower the students by the loudness of your voice or the use of threats. These should be a combination of sounds, actions and posture that make it clear that you want to speak. They should be taught with an explanation of how they are expected to respond.

Examples of sounds that you might use include tapping on a water glass, ringing a small bell, or using a chime or tone; or playing the distinctive ringtone on your phone.

ADD to this a physical signal such as raising your hand and ask students to amplify that signal by raising their own hands. Sometimes teachers who use these cues accompany them with a 3-2-1 sign with their fingers.

At the same time, make sure that your physiology expresses a clear message that you are waiting for their attention and expect it!

Whatever signal you decide to use, PRACTISE the signal over and over again with the students until there is no doubt about what you want and what they should do. Try to make these practices a game. Explain why you are using this behaviour to replace other ways you have gained attention in the past.

I am sometimes told that these 'low-key' signals will not be effective in the robust setting of a public high school. "That's all too 'rotary club' for my school", as one deputy principal told me.

This is one of the many paradigm shifts involved in transforming the culture and expectations of a class or school. I have observed teachers, in a large high school, who were unable to gain the respectful attention of 25 students however loudly they yelled. Yet, in the same school, a senior student would stand in front of one thousand students at a school assembly and establish quiet within a few seconds by raising her hand and standing erect and expectant.

END the practice of raising your voice, shouting, or using loud or violent noises to attract students' attention.

Although these are common approaches they are exercises of 'power over' and they usually raise the noise level instead of diminishing it. In attempting to rise above the hubbub of an excited group of students, it is all too easy to add to the noise and escalate it. What is needed is a contrasting sound that can be heard through the voices. It need not be loud to achieve this.

Trying to overpower the students to get their attention is also psychologically and physiologically harmful to the teacher. It increases frustration, raises blood pressure, and quite easily interferes with the teacher's own self-control.

5

ADOPT A way of establishing clear boundaries for student behaviour. Boundaries are different from rules. Boundaries establish ways of distinguishing between what is responsible (inside the boundaries) and what is not responsible (outside the boundaries).

There are several ways to set boundaries and I have listed four. All take some time to set up, but they will repay the time taken in the degree of cohesion and certainty that are established in the classroom. In all 4 cases, once the boundary is established and understood, students will be expected to use it to self-evaluate their own behaviour.

A simple boundaries activity, often used by teachers, is to establish Your Job/My job and not your job/Not my Job.

The Questions the teacher might ask:

Is that your job?

Whose job is that?

Do you know what your job is?

Please will you do your job and stop doing what is NOT your job.

Another is one of the variations of above the line/below the line – where behaviours that are above the line are responsible and those below the line are not. Marvin Marshall's 'raise responsibility' practices (https://withoutstress.com/ ) are a way of refining this, though my preferences are more descriptive than his ABCD identifications. I prefer 'Responsible' and 'Cooperative' as above-the-line descriptors and 'Interfering' and 'Disruptive' as below-the-line descriptors.

Questions from the teachers for the student will then be:

Is what you are doing above or below the line?

Do you know what to do to be above the line?

A refinement of this (and probably an improvement), is the 'Inside and Outside the boundary' way of describing what is, and what is not acceptable and responsible behaviour.

As with the previous strategy, create the 'Inside and Outside' through a series of collaborative discussions with the class.

You may want to use a class meeting style to hold this discussion.

Once you have negotiated what is inside and what is outside, and taken the time to explore meanings so that all the students have clarity about each, the questions for the teacher to ask can be:

- Is that inside or outside the boundary?

- What would be a way of getting what you want but staying inside the boundary?

Finally, there is the 'Window of Certainty' process for establishing boundaries. This is the most effective way of establishing shared purpose and common principles with both adults and children. The four 'frames' of the Window are clear boundaries.

Purpose: (where are we going both as individuals and as a class?)

Outcomes: (How will we measure our success?)

Beliefs: (What do we believe about how to achieve this success?)

Values: (What is the culture and the ways of working with each other that will support our success?)

For more on 'The Window of Certainty' go to the book or ebook advertised on the home page on this website.

Self-evaluation questions might be.

Are you inside the boundaries?

How can we help you back inside the boundaries?

AVOID setting up rules and consequences. Rules are mostly of the form 'Don't do this' and consequences are disguised threats (If you break the rule this will happen to you).

Expectations are a little better if they are framed as positives, but they are one-dimensional. They give information about what behaviour is wanted, but not what will be regarded as not responsible or needing improvement.

Using processes which differentiate between responsible and helpful behaviour, and the alternative irresponsible and unhelpful behaviour makes the nature of the choice clear.

Embedded in all three of the processes recommended above is strengthening the students ability to self-evaluate and the implication that it is they who control their own behaviour.

6

ADOPT a clear definition of responsibility within the class.

You can initiate this by mentioning the ambiguity of the word. Even young children notice that when adults urge them to be responsible they do not always mean the same thing.

With children in the youngest grades, it is acceptable for the teacher to offer a definition of responsibility and then discuss it with the children so that the definition makes sense to them.

With older children you may be best served by conducting a Classroom Meeting or Quality Circle about the meaning of responsibility:

The 3 steps of a classroom meeting are: DEFINE. PERSONALISE. CHALLENGE

Step 1: DEFINE responsibility. Accept inputs from all students and keep summarising. You are aiming for is some version of:'what responsibility means in this class is everyone getting what they need to do well and be happy without interfering with other people's ability to do well and be happy.' You will notice that the discussion always trends in this direction.

Step 2: PERSONALISE the definition by asking students to talk about what it would mean to them if all students and the teacher behaved responsibly.

Step 3: CHALLENGE the students to think and talk about the difficulties of establishing the expectation that every student is responsible for behaving responsibly and that the teacher's job is not to command them but to ask them: "is that responsible?"

END any reliance on commanding, guilting, threatening, or manipulating the students when they are not behaving responsibly.

When student behaviour is interfering with your teaching and with students learning simply ask:

1. 'What are you doing?'

2. 'Is it responsible?'

3. 'Do you know what you should be doing?'

4. 'Can you do it?'

Use a calm, non-threatening tone of voice.

When they begin to behave responsibly say: 'Thank you'.

7

ADOPT a 'let's work it out' approach when a student is choosing unhelpful behaviours.

Working it out

Asking the student to identify and STOP the Behaviour that is irresponsible or inappropriate. (What are you doing? Is that helping me to teach or you to learn? Is that inside or outside the boundaries we agreed? Can you please stop doing that and work out with me something that you can do instead?)

Identify the Replacement Behaviour that you want: one that will appropriately match classroom expectations and will be a better way to satisfy the Basic Needs than the unhelpful behaviour.

Negotiate a good plan with the student. One that:

.......is need-satisfying for both student and teacher.

.......has a realistic chance of success.

.......is attractive and specific.

.......is practised if necessary.

Determine the next step:

a) when the plan works.

b) if the plan doesn't work make a time to have a longer conversation.

Traditional classroom management tends to focus on

"Stop that! And if you don't ..........."

The strengths of the "Work it out" approach are that:

- It accepts that the traditional steps are a small part of the classroom management process.

- It recognises that all behaviour is purposeful.

- It focuses on the necessary but difficult steps that are important in helping the student learn replacement behaviour.

AVOID spending time telling the students what you don't want and expecting this alone to make a difference.

Change the focus of your conversation with a student who is behaving irresponsibly from what you DON'T want to what you DO want – as in the 'working it out' process. The human mind does not process a negative very well. Time talking about what you don't want simply emphasises that behaviour.

You can use the skill of flipping to help identify the positive want that is related to the unwanted behaviour.

Following on from this use the Responsible Self-management Questions as illustrated below. (Also see the RT pages on this website).

8

ADOPT the practice of replacing Commands with Questions

Questions communicate with the cognitive brain.

Commands activate the brain stem: the most primitive part of the brain.

Using questions to replace coercive or critical language is a key feature of effective brain-to-brain communication. When you ask a student a question, their brain processes your query through their frontal cortex. That is their brain's directive system. This increases the chances of their own directive system responding and taking on control of their behaviour.

As the left-hand side of the diagram below illustrates, asking questions puts us in communication with the students' cognitive brain and is conducive to learning.

Asking questions with an enquiring tone (tone is important) and a receptive body language (physiology is important too) you are most likely to achieve a cognitive response from the brain of the student.

In making the change from command to question what you are attempting is to avoid language and behaviour that implies that you are controlling the student and replace that language with questions that make it clear that you expect the student to responsible for their own behaviour.

Questions transfer responsibility to the respondent, as you will notice from the question sets suggested on this website.

AVOID the habit of command. Commands and other controlling language, such as bossing, accusing, criticising, or remonstrating with the student can be perceived as a threat to the student's autonomy and self-control (especially if the student has developed the habit of opposing teacher control).

A command, or any kind of 'telling what to do', is processed by the brain as an external imposition. Because everyone has both a protective need, and a need for autonomy, being 'bossed' by another person can be experienced as a threat which is processed by the brain stem - the most primitive part of the brain. When a teacher uses language that generates a response from this primitive brain area, the chance of resistance or 'push-back' is increased. The brain seeks to protect itself from invasion by the teacher's will.

Of course, it sometimes appears to be effective. Some students will respond to commands with compliance. In them, the brain's protection system is initiating another kind of protective response – submission or avoidance of conflict.

The spectrum of responses to controlling behaviour is a familiar part of the experience of most teachers and managers. A few do as they are told willingly, others do as they are told but respond with the minimum effort asked of them, others do as they are asked resentfully, and a few react with defiance. It is all boringly predictable once the brain is understood.

It is far easier for a teacher who wants both productive behaviour by the students AND enhanced student self-management to take all the complications out of it. It is as easy to ask: 'What are you doing?' and 'Should you be doing that?' as it is to say: 'Stop that and do as I tell you!'

9

ADOPT your own repertoire of the 'Responsible Self-Management Questions'. These are based on Dr William Glasser's 'Reality Therapy Procedures'. Their intention in this context is not therapeutic, they are simply very useful questions for helping a student to identify and evaluate their present actions, and then identify an alternative and more useful behaviour.

- What are you doing? Students can't always identify their own unhelpful behaviour, but always ask.

- Is it responsible? (or is it what you should be doing right now? / or is it what I have asked you to do?)

- What else can you do? (or What should you be doing? or What could you be doing? What would be a better way to get what you want without disturbing other students / or disrupting the lesson)

This is the brief version. The three questions can easily be fitted into a brief classroom interaction and are often enough to be effective as a simple redirection for the student.

However, a longer version, which takes a little more time may be needed to help you, and the student conduct a deeper exploration of the purpose of the student's behaviour.

- 'What are you doing?'

- 'What do you want to achieve through that behaviour?' (or 'What do you want to happen next?' or 'Where do you want that to take you?' or 'What is your purpose or intention?')

- 'Is what you are doing getting you what you want?' (or 'Is it likely to lead to good outcomes for you and for the class? or 'Is it the best way to get what you want?' or 'Is there a better way?' or 'Is it helping or hurting?

- What else can you do? (or 'Is there a better option?' or 'Can we find a way to get you what you want and also look after the learning needs of everyone in the class?' or 'Have you noticed what other students do and that works well in the same situation?'

- As the right-hand side of the diagram below illustrates, asking questions puts us in communication with the student's cognitive brain and is conducive to learning.

Using questions to replace coercive or critical language is a key feature of effective brain-to-brain communication. As we saw in the previous section, when you ask a student a question, their brain processes your query through their frontal cortex. That is their brain's directive system. This increases the chances of a cognitive response and of the student taking control of their own behaviour.

AVOID the habit of command. Commands tell the student that the teacher expects to control them. Questions imply that the student is, and should be, in control of their own behaviour.

10

ADOPT the use of Assertive Practices (Authoritative leadership). These let students know what you want and expect. They support goal-directed and responsible behaviour.

Establish the purpose of taking personal responsibility.

Set Clear boundaries.

Assertive practices include:

- Saying what you want and why.

- Listening for meaning and acknowledging difference.

- Using 'I' statements.

- Applying the 'Broken Record' technique.

- Using 'Fogging' to deflect criticism.

Assertive directing

Applying Consequences such as time-out ……

Influencing and Persuading

Using and teaching Connecting behaviours.

Showing you care about students.

Listening

Encouraging

Showing respect and Respecting differences

Being supportive.

Teaching replacement behaviours.

Practicing unconditional positive regard.

Negotiating problems

Trusting

Building Capacity

Inspirational and enthusiastic teaching

Coaching and Counselling

Flipping from negatives to the positive

Teaching the 'hows' of self-management

You will have to supplement these assertive practices by drawing clear boundaries between what is responsible and constructive behaviour and what is not. Then as the boundary-rider in the classroom, you will insist that there are natural consequences for students who step outside the boundaries.

This is not just a language change, (though the change in language is very important). It is a very powerful change in the locus of control.

The shift is from teacher in control to students and teacher self-controla gainst a mutually agreed standard of behaviour.

As the teacher, it is your job to teach students how to make this shift. If the classroom is to be an effective place of learning, teaching students how to behave responsibly is as important as curriculum content and process, perhaps even more important, because when students manage themselves the rest of the teacher's tasks are not complicated by the struggle to control students.

Learning, as the later pages on brain and mind will show, is an internal process that cannot be controlled from outside the self. Give up thinking that useful learning and human development is anything like the 'conditioning' of rats or dogs. You may have been taught the outdated psychology of external control during your teacher education, but it will be of no use to you when you are working with the complexity of the human will in the school classroom.

AVOID coercive practices (attempts to 'make' students do things by imposing painful controls):

Punishment

Rewarding to control

Threats

Withdrawing privileges

Detention

Manipulation

Coaxing

Loss of status

Isolation

Punitive consequences

Sarcasm or 'Put-downs'

Public Criticism

Violence

Brainwashing (using manipulative propaganda)

Emotional blackmail

Systematic ignoring

Nagging

Isolation

Punitive time-out

Suspensions

Repetitive writing tasks (lines or rules)

Menial tasks (Picking up rubbish etc)

It's quite common to combine some of the practices above into systems such as levels systems, 'assertive discipline', PBL (Positive Behaviour for Learning) or the Responsible Thinking Process. There are positive features of some of these systems, but they are distorted when used coercively.

Notes:

The difference between coercive and assertive practices is profound, not so much in their detail as their intention.

The intention that drives assertive behaviours is to establish and maintain the conditions required for learning and personal improvement. Students are challenged to take charge of their lives and learning.

Imposing pain with a coercive intent is focused on establishing who is in charge in the classroom. It assumes that the teacher should be in control in the classroom and is justified in imposing pain or withholding pleasure to achieve that end.

The assertive teacher may sometimes use similar strategies to the coercive teacher. They may use consequences to maintain firm boundaries between responsible and disruptive behaviours or use 'time out' and temporary suspension to provide an opportunity for reflection and new choices.

These differences in intent transform the way the strategies are experienced by students. Assertive teachers are 'warm demanders': they combine high expectations with genuine care for the students.

Avoiding or reducing the use of coercive behaviours means that you will minimise or eradicate all threats, punishments, and manipulative rewards as the means to compel students to behave responsibly.

It DOES NOT MEAN that you will stand by helplessly while students behave irresponsibly. The self-managing classroom is not an invitation to anarchy!

I don't mean to imply that there is anything easy about making this shift. Relinquishing controlling behaviours is the hardest part of creating a self-managing classroom. However, it is the most necessary step of all those listed in this book.

Behaviours that are controlling or coercive have 4 inhibiting effects on the creation of a self-managing classroom culture:

- They damage relationships.

- They communicate the expectation the teacher alone is responsible for managing behaviour.

- Because autonomy is a universal genetic need, they create the resistance that teachers experience when they try to manage students.

- They communicate lack of respect by the teacher.

11

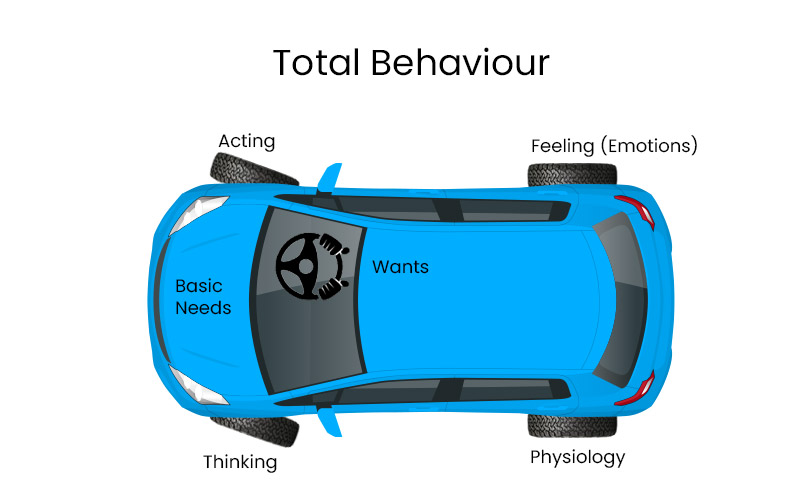

ADOPT a simple explanation of human behaviour through the behaviour car metaphor. Just as the car has 4 wheels, behaviour has 4 elements: Acting, Thinking, Feelings and Physiology.

Students generally do not have a language with which to de-mystify self-control. Generalised instructions such as 'behave yourself' or 'control yourself' are no help because they are neither specific nor informative.

The car metaphor provides students with language and a visual concept that makes it possible to discuss specific behaviours and to talk and think about what to do to self-manage.

Dr William Glasser, who devised the 'behaviour car' metaphor regarded it as one of the most creative ways of helping people to understand and control behaviour that he conceived.

When I present the behaviour car to students, I usually ask them to develop it for themselves by asking them:

1. What are the differences between thinking and acting?

| Thinking | Acting |

|---|---|

| Ideas | Doing |

| Reasons | Moving |

| Talking to yourself | Walking and running |

| Planning | Using your body |

| Reflecting | Performing a skill |

2. The words students come up with will be age-related, but they enable me to ask the questions:

- Which can you see, and which is invisible?

- Is an intention a thought or an action?

- What do you try to achieve with your thoughts and actions?

3. These questions invite discussion and can then be connected to the car by comparing them to the front wheels of the car. The front wheels of the car steer it so that it goes where the driver wants it to go. In the same way the 'front wheels' of our behaviour are our best attempts to get what we want.

4. Next, I introduce the back wheels (often at a different time) so that I can use 'front wheels' language with the class for a while before I introduce the back wheels. Once again, I initiate examination of these elements of behaviour with a question such as: What are the differences between thinking and feeling?

5. When students have identified differences between thought and feeling I ask questions that help them to understand the significance of the difference:

- Can you control how you feel as easily as how you think?

- When you are angry or sad, can you just tell yourself to 'cheer up'?

- Which feelings give us energy? Which ones take our energy away and lead to us feeling 'down'?

6. It's then easy to teach that emotions are like our back wheels. They change the amount of energy or drive in the car, but they are not good for steering. Because emotions are our energy meter, they also let us know how we are feeling and send us signals about whether we are in control or not.

7. Once students are talking about emotions, I introduce physiology or 'body state' by asking what is happening in our body when we are experiencing different emotions. By using examples such as excited, angry, worried, confident, daring, or bored, I ask students to demonstrate the physiology that accompanies each different emotion.

8. From this point on the students have enough information for me to be able to teach the remaining key concepts of the behaviour car which are:

A. All behaviour is TOTAL – our acting, thinking, feeling and body state are always connected. If we change one, the others change as well.

B. Although we can't control our back wheels directly, they will change if we change our front wheels. Managing our thinking and acting is the key to self-control.

C. Naming our behaviour using the language of the behaviour car, enables students to identify the element of behaviour they need to focus on to manage themselves well in any situation.

Once the car metaphor is firmly established with a class or a student, it generates very specific and helpful questions that help students manage their behaviour and learning. These questions might be:

- Are you on your back wheels or front wheels?

- Do you know what to do to change your back wheels?

- What kind of thinking helps you to do your best work?

You can add to their understanding by using your own knowledge to explain to students why you are using 'brain breaks', or energisers, or why you set up classroom routines so that students bring their best energy to learning.

AVOID the use of vague phrases such as 'behave yourself'.

Everyone is always behaving (there is always thinking, acting, feelings and physiological state happening) so this kind of imprecise language will not help students to identify the elements of behaviour they should focus on to improve their management of self.

Replace vague injunctions with more specific and car-related questions:

- Which wheels are you on?

- Are you on the back wheels or the front wheels?

- Do you need time (or help) to get off the back wheels?

- Which wheel will help you move forward responsibly?

12

ADOPT The expectation that students will set personal goals.

Whenever they are faced with a task, ask students to predict how they will perform at the task and make that the benchmark for discussion with the student. As John Hattie says: 'Human nature is for them to play safe in their prediction. When they exceed their forecast, their belief in themselves as a learner increases. This ratchets up over time and their expectations of themselves rise.'

This has the highest-ranking effect size in all of Hattie's findings.

Develop ways in which the students keep records of the goals they set themselves, and how they perform against those goals. I used to ask students to track their goals on a simple planner to which only they and the teacher had access. (Students respond to personal and private goals in a very different way to public displays of the same which often create competition".

At the same time ask the whole class to set goals for any aspect of class performance that you can measure and which will encourage collaborative and supportive behaviours.

AVOID the perception that student results and profiles are teacher business.

As well as your records, make sure that students have their own records of their progress and that they update them after every assessable task.

Provide reflective time when students review their achievements profiles against the goals that they set themselves. Celebrate success by inviting students to write a note to their parents describing what they did (countersigned by the teacher).

When students do not achieve the goal they set themselves, provide peer-to-peer or teacher-to -student conferencing to pinpoint specific areas for improvement.

Review class goals whenever there is cause for celebration, or the need to reflect on the goals when they are not being achieved.